Jim Tyler looks back on 40 years with the magazine, and on the technoloical advancements made in airgun and accessory manufacture since he wrote his first article on home-made scope rails!

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

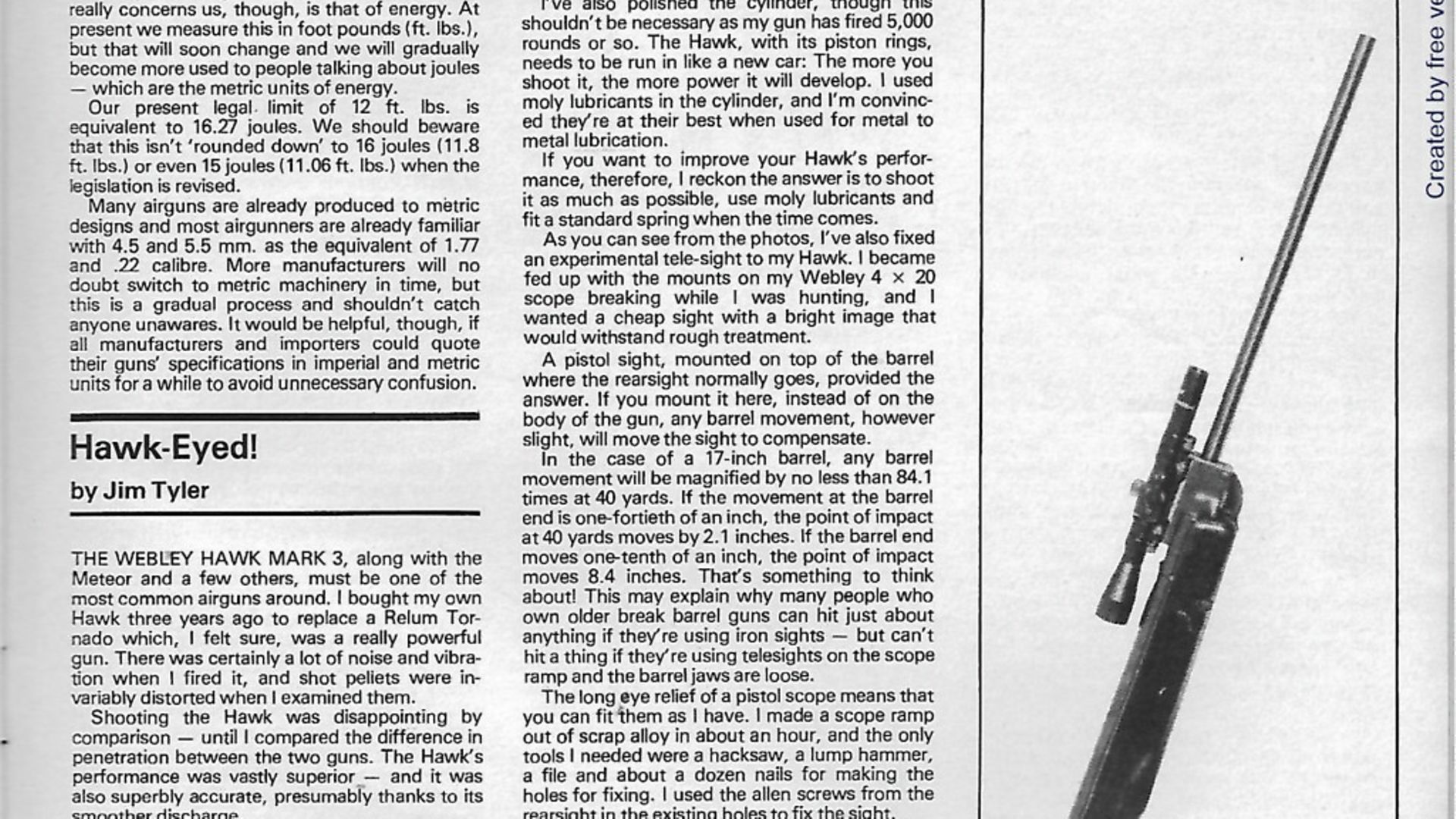

If you had bought the October edition of Airgun World 40 years ago, you might have noticed a short, two-thirds of a page, article entitled ‘Hawk Eyed’ written by some unknown called Jim Tyler. The article described making a short scope rail that could be bolted onto the breech block of a Webley Hawk Mk.3 in place of the rear sight, and onto which a 1.5 x 15mm pistol scope with long eye relief could be mounted.

The article had been inspired by the prohibitive cost of half-decent, one-inch body tube scopes and mounts at the time, and the dreadful optics and build quality of more affordable scopes with ¾” or 7/8” body tubes and flimsy, pressed steel mounts that simply could not hold the scope in position on a lively springer. The lightweight 1.5 x 15mm pistol scope gave a brighter, clearer image, with two further key advantages; it gave very fast target acquisition, and being bolted to the breech block, pointed in the same direction as the barrel if the breech jaws permitted lateral movement.

The idea must have had some merit because shortly after publication, a letter was received from Webley & Scott, claiming to have thought of it first and, sometime later, the ‘Webley Teleskan’ appeared, and sold well for a while, until 1” body-tube scopes started to fall in price, John Ford launched the Sportsmatch range of high quality and affordable mounts, and the Teleskan slipped quietly into airgun history.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Scopes

John Ford was one of the most influential people in the last 40 years of the sport, because before Sportsmatch appeared, a set of decent quality mounts could cost as much as, even a multiple of, the price of the scope with which they were to be used. In my opinion, it is no exaggeration to say that the availability of affordable scopes and mounts ushered in the modern age of airgun sport, in which outdoor target shooting could flourish, and which gave a degree of accuracy that highlighted some of the shortcomings of contemporary airguns and pellets.

Not long after John Ford had introduced his scope mounts, the importers of scopes discovered parallax error, and offered a solution in scopes with adjustable objective lenses. Truth be told, such was the standard of accuracy of many of the airguns and pellets in use at the time, that the contribution to inaccuracy due to parallax error was the least of our problems, but as the new sport of field target grew, it drove improvements in the standards of rifles and pellets to the point at which parallax error was a major consideration.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Reticles

Another step forward in scopes that was largely driven by the demands of outdoor target shooters was the emergence of multiple aim point reticles, replacing the standard cross hair or duplex reticles, both of which forced the user to ‘aim off’ for targets away from their zero range or point blank range (the distance between the nearest and furthest points at which the user could aim dead on, and be acceptably close to the target POI), Multiple aim point scopes gave precise aim points for ranges well away from the zero, again highlighting shortcomings in contemporary airguns and pellets.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Pellets

A glance at the pellets used by the winners of the 1980 Airgun World/Sussex Armoury national field shoot reveals, perhaps surprisingly, that seven of the top ten were using flat-head pellets that were very susceptible to wind drift, two were using pointed pellets that were little better, and only one was using round-head pellets, and the reason is that most round-head pellets of the time were of very poor quality.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Flat-heads

Taking the three pellet types in order; flat-head pellets can be extremely useful in airgun hunting because by having lower penetrative qualities than pointed or round-head pellets, they create a much greater impact force, and create a wider wound cavity that displaces more tissue, both of which aid humane kills. Unfortunately, flat-head pellets have very high drag in flight, and so lose velocity and energy more rapidly than more aerodynamic pellets, which also makes them much more susceptible to wind drift. Wind drift is no problem to the airgun hunter, because he can simply choose not to shoot in strong wind, but competition shooters have to take their shots, irrespective of whether the air is still or storm force, and that’s why these days, the only target shooting where you will only find flat-head pellets in use is indoor target shooting, where there is no wind.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Pointed

Pointed pellets were heavily marketed in the late 1970s and early 1980s on their supposed enhanced penetrative properties, which had they been true, can be counterproductive in hunting because the greater the penetration, the lesser the impact force. Perhaps the uptake of pointed pellets by airgun hunters was due in part to the relatively low muzzle energies of many airguns, and a perceived need to compensate with pellets that could penetrate more. However, because they are intrinsically less accurate than round-head pellets, their use in field target would only last as long as it took for pellet manufacturers to introduce round-head pellets made to the same standard.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Round-heads

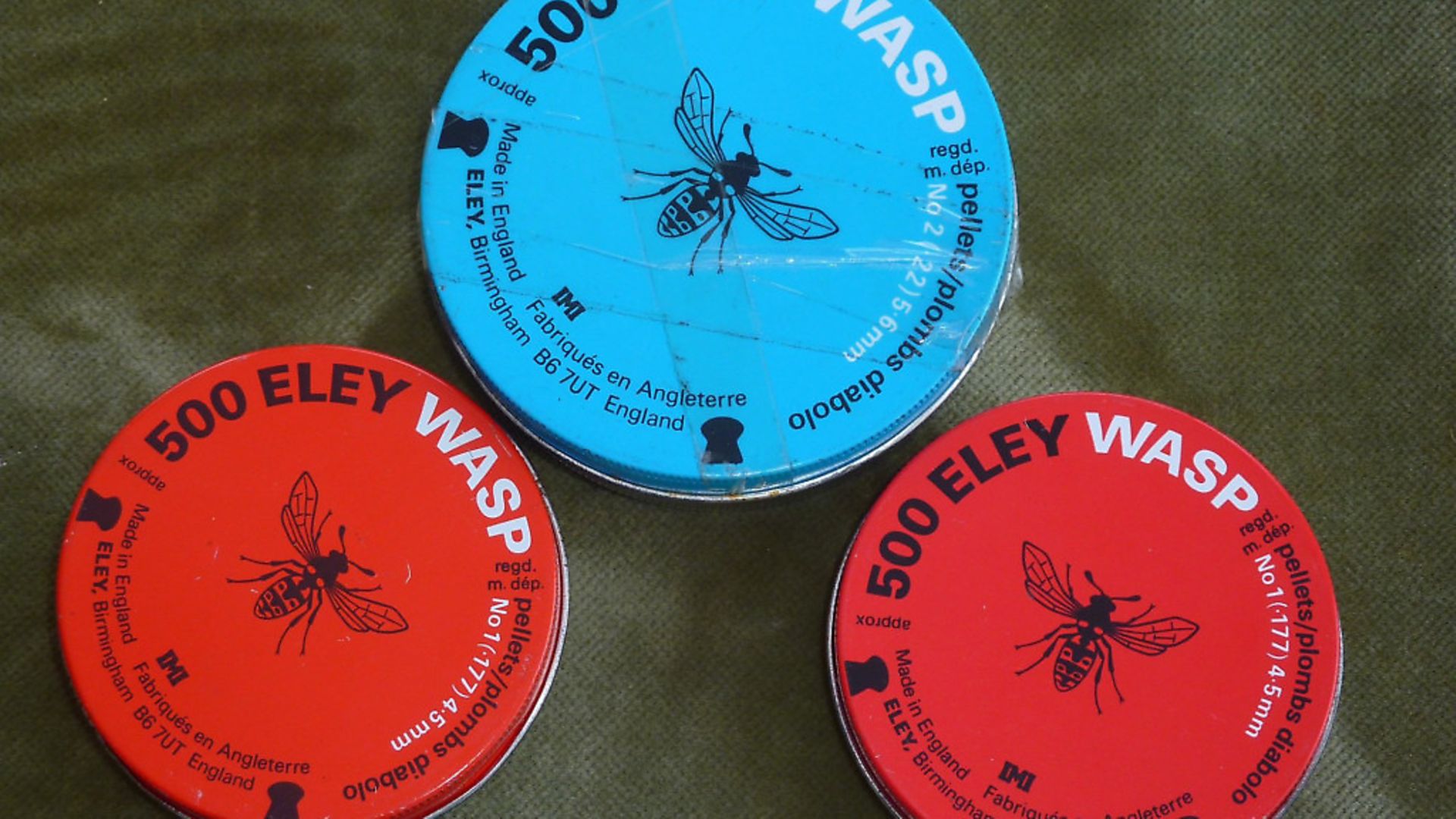

The best of the round-head pellets of the early 1980s was the Eley Wasp, a very hard, lightweight pellet with an extremely high start pressure, courtesy of its hardness, and probably the only UK manufactured pellet with quality control to match its continental rivals. A big change came when German manufacturer RWS introduced a round-head pellet with the quality control of its Superpoint, called the ‘Superdome’. The 8.3 grain Superdome became the de facto standard field target pellet, before being joined by H & N’s FT Trophy and the Premier round-head pellets from USA manufacturer Crosman, but the real revolution in pellets was still some years off.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Common feature

All of the pellets on the market had one thing in common, which was high start pressure, due to their hardness and the thickness of their skirts. Forty years ago, many of the spring airguns in circulation had short cylinders and hence piston strokes, and needed autoignition (dieseling) to get the pellet moving early enough in the piston stroke for the high start pressure pellet to be accelerated up to speed.

The revolution in pellets, certainly as far as outdoor target shooting was concerned, was the introduction of a round-head pellet manufactured in Czech by JSB and sold in the UK as the Air Arms Diabolo Field, a pellet that had a far lower start pressure – between a half and a third that of all contemporary pellets – courtesy of its soft composition and thin skirt, and it was a pellet that was made with a degree of precision as high as they came.

These days, most adult springers have longer strokes than many in 1980, and are able to achieve satisfactory muzzle velocity without need of dieseling, so they can perform well with harder pellets, and whilst soft pellets seem to dominate outdoor target shooting, some springers still give their best with quality round-heads made by the likes of H&N, RWS and Crosman.

PCPs

The PCP was nothing new back in 1980, but if you wanted one, the choice was either a Daystate Huntsman, or you could opt for a Daystate Huntsman, and it was very expensive in its own right, more so after the cost of a charging system was added, so the PCP was a very rare sight on the early FT circuit.

In the early 1980s, the Huntsman was joined briefly by the Galway Fieldmaster, after which, the PCP went through years of sometimes rapid development, with luminaries such as Mick Dawes introducing his regulator, John Bowkett designing the Titan then BSA PCPs, Air Arms joining in the fray and becoming the leading player they remain to this day, and the Rapid 7 from Theoben. Other influential figures included Shaun Hill of ISP, Dave Welham effortlessly transferring his springer tuning skills to the PCP, and that man John Ford again, this time bringing Gerald Cardew’s design to the market in the ahead of its time CG2. There were more, many more, and that’s just the UK!

Modern PCPs have evolved to the point at which some are practically ‘dead’ when shot, and it is questionable whether even entry-level PCPs have almost de-skilled airgun shooting. An outdoor shooter using a top competition PCP still has to gauge the range, the wind and its effect on the pellet in flight, but if they master those, it takes some incredibly poor technique to miss.

PCPs have come a long way in 40 years, and it’s difficult to see how they could be refined much beyond where they now are.

Spring airguns

Compared to the rapid developments seen in PCPs, in my view, the springer has practically been at a standstill these last 40 years, and the last significant innovation as far as I’m concerned was the adoption of synthetic piston and breech seals by Feinwerkbau in the late 1970s. True, the very low muzzle energy of many 1980 springers is a thing of the past, and tuners are always coming up with ideas that they think will improve the springer in some way, but it’s difficult to find anything genuinely new, that hasn’t been done before;

Short stroke/long stroke, light piston/heavy piston, stiff spring/soft spring, short/long/thin/fat transfer port, parachute seal/‘O’ ring, thin cylinder/fat cylinder – you name it, and someone, somewhere, has already done it.

Talented people

That’s not to say there have not been very talented designers, engineers, and even the occasional genius involved with the springer, such as John Wiscombe with his opposing piston recoil rifles, or Ken Turner with the beautifully elegant TX200, and others.

So why could it be that PCPs have come on in leaps and bounds, whilst springers trod water for four decades? I think there were two reasons; first, the spring air rifle had already evolved as far as it was possible, certainly after the 1983 debut of the game-changing Weihrauch HW77, which itself was nothing new. The superb Rekord trigger had been around since the 1950s, and the sliding cylinder concept had been done before. Weihrauch simply put together tried and tested design concepts in a combination that happened to be near perfect for our 12 ft.lbs. limit.

Lack of complication

The other reason I believe the PCP has seen far greater innovation is that the physics that underlie the working of the PCP are incredibly uncomplicated compared to those of the spring airgun.

The PCP has a reservoir of densely packed air molecules contained in either the cylinder or a regulator, and shooting the rifle entails merely releasing a certain mass and density of the air molecules behind the pellet; the air molecules collide with, and bounce off the rear of the pellet, imparting a little of their momentum in the process, and because there are many times more air molecules acting on the rear of the pellet than the front, the pellet obligingly moves up the barrel.

Shooting simplicity

Shooting the PCP involves merely opening a valve to an extent and for a duration sufficient to get the pellet up to speed, and opening the valve takes relatively little energy, usually provided by a spring-driven hammer or striker, which weigh so little, and with such short travel, that any recoil they cause is a fraction (perhaps a quarter to a fifth of a millimetre) than that of a springer. This means that you can happily experiment modifying just about any of the components, within bounds of reason, without significantly adversely affecting the shot cycle, or accuracy, allowing R&D to be carried on in the knowledge that there would be no significant ill effects.

Dynamic internals

In contrast, inside the highly dynamic springer, every modification has ramifications, which usually translates into drawbacks as well as improvements, and in many cases, the drawbacks would have been more significant than any gain. As Mike Wright often said, ‘in the springer, everything affects everything else’.

As manufacturers and tuners try to improve one aspect of the springer shot cycle, they almost inevitably degrade another aspect of that very cycle and whilst the better manufacturers thoroughly test (10,000-plus shots) any alterations, to ensure that they genuinely give an improvement before releasing them into the market place, I’m afraid some tuners are less assiduous.

So, in the past 40 years, scopes have evolved and improved considerably, pellets massively, PCPs appreciably, and springers hardly at all.